When it comes to body fat, most of us think in terms of “how much,” but the type, location, and function of fat matter just as much—if not more. Understanding the science behind fat storage reveals why two people with the same body weight can have vastly different metabolic health outcomes.

Fat Cell Growth: Hypertrophy vs Hyperplasia

Fat cells (adipocytes) can expand in two ways—hypertrophy, where existing cells grow larger, and hyperplasia, where the body creates new fat cells. Hypertrophy is typically the first stage in weight gain and is considered more metabolically harmful. Enlarged fat cells become dysfunctional, inflamed, and more insulin-resistant, releasing excess free fatty acids into circulation. This contributes to elevated blood sugar and systemic inflammation.

In contrast, hyperplasia is the body’s protective mechanism. Creating new, smaller fat cells allows for more efficient fat storage with less metabolic stress. These smaller cells tend to remain more insulin-sensitive and capable of safely storing lipids. However, not everyone has the same capacity for hyperplasia, which may explain why some individuals develop insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes more readily than others.

Visceral vs Subcutaneous Fat

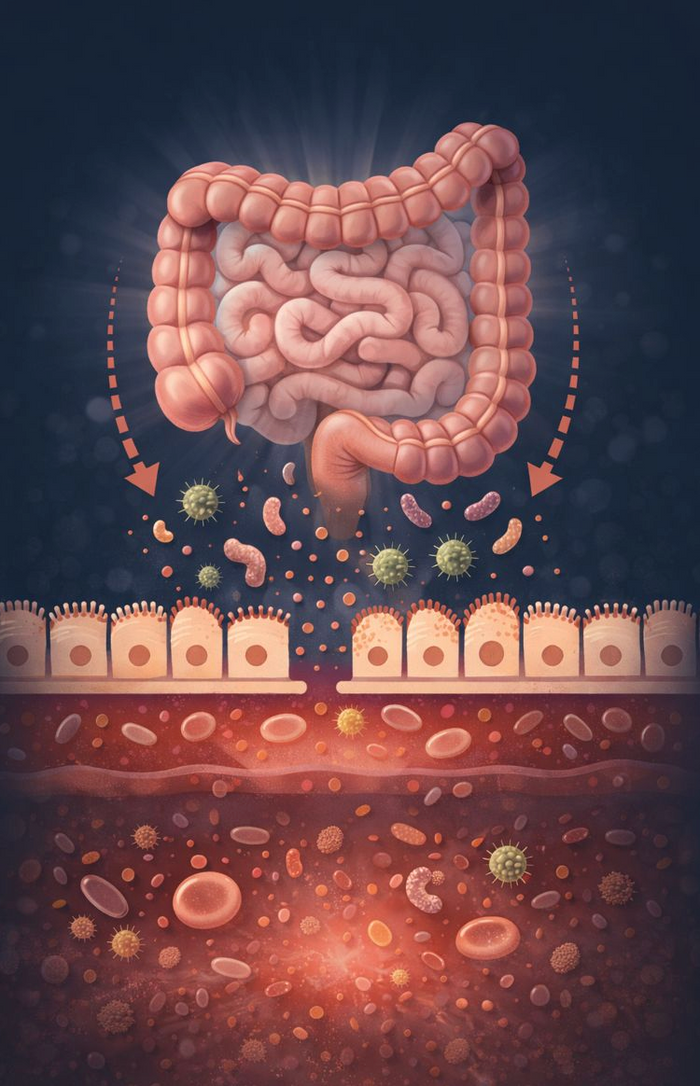

Where fat is stored is just as critical. Subcutaneous fat sits just under the skin and, while not ideal in excess, is relatively benign from a metabolic perspective. Visceral fat, however, accumulates deep within the abdominal cavity, surrounding vital organs like the liver and pancreas. This type of fat is more metabolically active—and not in a good way. It secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines and contributes to insulin resistance, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

The Problem with Ectopic Fat

When fat storage exceeds safe limits, especially in the case of hypertrophied fat cells, excess fat spills over into places it doesn’t belong—like the liver, muscles, heart, and pancreas. This is known as ectopic fat storage, and it’s a hallmark of severe metabolic dysfunction. Fat in these areas impairs organ function and worsens insulin resistance.

Fat Cell Insulin Resistance

Healthy fat cells respond to insulin by storing fat. But when fat cells become insulin resistant—usually due to chronic over nutrition and inflammation—they stop taking in fat efficiently and begin releasing fatty acids into the bloodstream. This worsens the cycle of metabolic dysfunction, as the excess fatty acids drive insulin resistance in other tissues like muscle and liver.

In short, not all fat is equal. The size, location, and metabolic health of your fat cells all determine whether fat is working for you—or against you.