If you’ve started tracking your Met-Flex Score using glucose and ketone readings, you might have noticed something surprising:

It can feel hard to reach the “Fat Mode” zone.

That’s not a mistake — and it’s not a problem.

In fact, it’s by design.

This article will help you understand what your numbers actually mean, why ketones often need to be higher than expected, and how to read your graph with confidence.

First, what is the Met-Flex Score?

Your Met-Flex Score is based on your GKI (Glucose-Ketone Index).

In simple terms:

- It looks at how much glucose (sugar) is available

- Compared to how many ketones (fat-derived fuel) are circulating

- And shows which fuel your body is mainly using at that moment

Lower GKI = more fat-derived fuel

Higher GKI = more sugar-derived fuel

This helps you see whether your body is:

- running mostly on sugar,

- mostly on fat,

- or comfortably using both.

Why does Fat Mode seem “hard” to reach?

Here’s the key thing most people don’t realise:

You can be burning fat without being in Fat Mode.

Fat Mode is not about any fat burning.

It reflects strong, measurable fat-derived fuel use — where fat is supplying a large share of your body’s usable energy.

That only shows up when ketones are clearly elevated, unless glucose is very low.

What the numbers actually look like

Here’s a reality check using common glucose and ketone values in mmol/L:

|

Glucose |

Ketones |

GKI |

State |

|

5.0 |

0.5 |

10.0 |

Glucose Mode |

|

4.8 |

0.8 |

6.0 |

Glucose Mode |

|

5.0 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

Glucose Mode |

|

5.0 |

2.0 |

2.5 |

Flex Mode |

|

4.6 |

2.5 |

1.8 |

Fat Mode |

What this shows is important:

- Even normal glucose with low-to-moderate ketones still lands in Glucose Mode

- To reach Fat Mode, ketones often need to be around 1.8–3.0 mmol/L

- Unless glucose is unusually low, higher ketones are required

So yes — it’s normal if Fat Mode doesn’t show up every day.

When do ketones usually get that high?

Ketone levels in this range typically occur with:

- Sustained low-carb or ketogenic intake

- Fasting or time-restricted eating

- Endurance-style exercise

- Advanced metabolic adaptation over time

They’re less likely to appear from:

- a single low-carb meal

- a “good” day of eating

- or short-term dietary changes

This isn’t a flaw — it’s a feature

The Met-Flex model is deliberately conservative, and that’s a good thing.

It means:

- Fat Mode is earned, not constant

- You don’t get a “fat-burning badge” just because carbs were lower for one meal

- Flex Mode becomes a healthy, achievable middle ground

In real life:

- Most metabolically healthy people spend most of their time in Flex Mode

- With short, intentional dips into Fat Mode

- And occasional time in Glucose Mode (which is also normal)

That pattern reflects true metabolic flexibility.

Here’s the simplest way to think about it:

“Fat Mode reflects strong fat-derived fuel use — not just normal fat burning.”

Or, put another way:

“You can burn fat without being in Fat Mode. This zone shows when fat is supplying a large share of your body’s usable energy.”

This helps keep expectations realistic — and progress motivating.

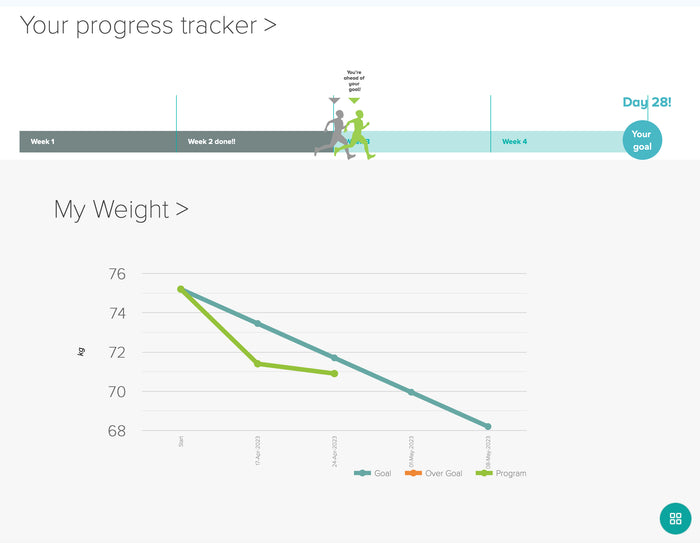

What you might see on your graph

- Glucose Mode: higher GKI, lower ketones — common after carbs, stress, poor sleep quality or late nights

- Flex Mode: moderate GKI — using both fuels efficiently

- Fat Mode: low GKI — usually appears during fasting, low-carb phases, or after endurance exercise

A typical healthy pattern looks like:

- moving between zones across the week

- not staying “perfectly” in one zone

Bottom line

You’re not doing anything wrong if Fat Mode feels hard to reach.

Fat Mode is intentionally hard to reach — because it represents meaningful, measurable fat-fuel dominance, not everyday fat oxidation.

The real goal isn’t to live there forever.

It’s to build the ability to move between fuel sources - and your Met-Flex graph helps you see that journey clearly.

You can order your Met-Flex bundle HERE.