Many of us treat late-night eating as a harmless habit. After a long day, dinner gets pushed to 8, 9 or even 10 pm. We tell ourselves “it’s fine — I’m eating well.” But emerging evidence suggests the timing of dinner might matter almost as much as what we eat.

Even if you consume the same calories, eating late consistently may quietly undermine weight goals, sleep quality and metabolic health.

What research tells us: the risks of late eating

Let’s walk through the strongest links between late dinners and health outcomes — and then translate them to what it might mean down under.

Weight, fat loss and body shape

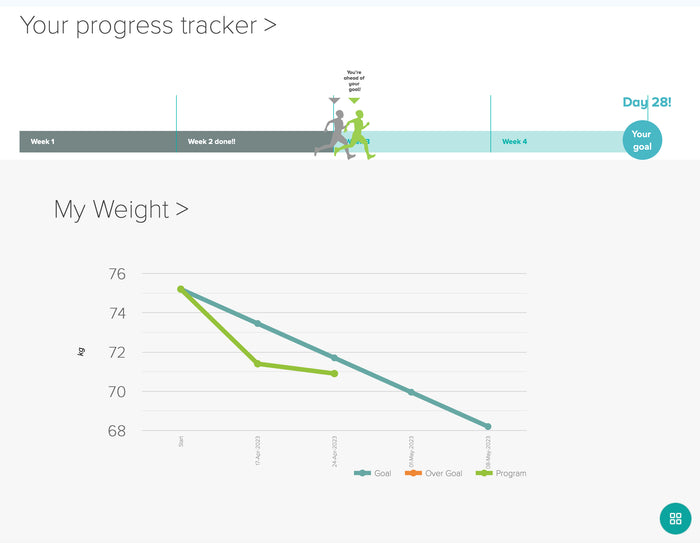

One of the clearest signals: shifting your calorie load earlier in the day tends to produce better weight-loss results, even when total energy intake is unchanged.

- In a 2024 meta-analysis pooling multiple trials, dieters who concentrated their intake earlier lost on average 1.75 kg more than those who saved more calories for dinner.

- In a classic trial of 93 women on 1,400 kcal diets: those with a big breakfast and light dinner lost ~8.7 kg over 3 months, compared to ~3.6 kg in the reverse-timing group.

- Another trial split by dinner timing (7–7:30 pm vs 10–10:30 pm) found the early group lost ~6.7 kg versus ~4.8 kg in the late group, with greater waist circumference reduction as well.

These are powerful signals: it’s not just about how much you eat, but when.

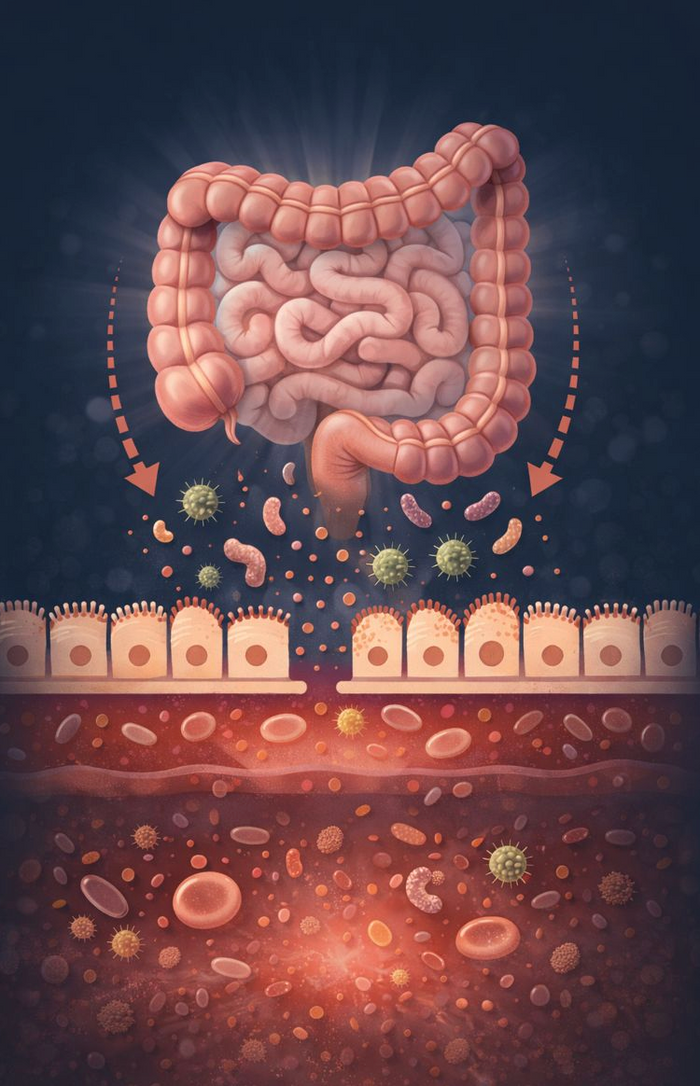

At a mechanistic level, late meals seem to:

- Lead to lower overnight calorie burn (because you’re mostly asleep)

- Flatten the thermic effect of food (your body burns fewer calories digesting food at night)

- Alter hormonal signals (higher ghrelin, lower leptin) that drive hunger the next day

- Activate gene expression favouring fat storage over fat burning

- Impair glucose handling — late evening insulin sensitivity is lower

A Harvard-summarised trial found that even when physical activity, sleep and other variables were tightly controlled, late eating conditions led to reduced leptin (satiety hormone), slower energy burn, and gene changes favouring adipogenesis over fat breakdown. hms.harvard.edu

In short: your body is primed to deal with calories earlier in the day — not as well later.

Diabetes and blood sugar control

Late dinners are consistently linked with worse glycemic metrics:

- Lab studies show that evening meals often produce higher glucose peaks and longer elevations compared with the same meals earlier.

- In a Korean cohort (22,700+ adults), eating after 9 pm was associated with ~18–20 % higher odds of developing type 2 diabetes.

- A U.S. NHANES study found every hour dinner was delayed was associated with a small climb in HbA1c (a long-term blood sugar marker).

- Among people who already have diabetes, late-night eating (after 8 pm) is tied to poorer glycemic control, elevated triglycerides, and lower HDL cholesterol.

The link: late eating seems to strain insulin dynamics and extend glucose exposure — giving your pancreas more to handle at a suboptimal metabolic time.

Heart and metabolic risks

Because late eating often drives weight gain, worsened lipids, and blood glucose disruption, it also indirectly increases cardiovascular risk. But even more directly:

- A Taiwanese study estimated that shifting just 100 kcal from after 8:30 pm into lunchtime could lower LDL (“bad”) cholesterol by ~1 %.

- Moving ~11 g of fat from dinner to breakfast could reduce LDL by ~5 %.

- In Japanese middle-aged adults, frequent late dinner + after-dinner snacking was associated with a ~49 % higher prevalence of abnormal blood lipids (cholesterol), 42 % higher abdominal fat, and 33 % higher metabolic syndrome.

- In the French NutriNet-Santé data, dinners after 9 pm (versus before 8 pm) were linked to a 13 % higher heart disease risk (though just shy of statistical significance) and a 28 % higher stroke risk.

It seems plausible that shifting your energy load earlier may gently lower certain cardiovascular risk factors.

Cancer, circadian disruption and chronic disease

This area is still emerging, but intriguing:

- A Spanish study found that eating dinner at least two hours before bedtime was linked with 16 % lower breast cancer risk and 26 % lower prostate cancer risk. For “morning people,” the benefit rose to 34 %.

- In the French cohort, dinners after 9:30 pm were tied to a 48 % higher breast cancer risk and more than double prostate cancer risk.

- A 2024 study observed that people eating within three hours of bed at least 4 days/week had ~2× odds of tubular adenomas (precancerous colon polyps), even after adjusting for other risk factors.

Why might this happen? Late eating disrupts circadian rhythms — meaning clocks in cells, metabolism, and DNA-repair machinery may misalign. Some DNA repair genes run on circadian cycles; if your rhythm is off, the timing of repair may become suboptimal.

While we can’t say late dinners cause cancer, the mounting associations make it a plausible modifiable risk factor.

Sleep disruption & acid reflux

Even if we set aside weight and metabolism, late dinners tend to worsen sleep and reflux:

- A national Brazilian survey found that eating dinner after 9 pm was linked to shorter sleep duration, longer time to fall asleep, and poorer sleep quality.

- Those who made dinner their biggest meal had 52 % higher odds of reporting poor sleep, and 34 % higher odds of insomnia.

- In Australia, a study of students showed eating within 3 hours of bedtime increased waking during the night by ~60 %.

- On reflux: people eating dinner <3 hours before bed were 7.5× more likely to experience acid exposure than those leaving ≥4 hours. Lying down soon after a full stomach is a known trigger for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms.

For many, an early, lighter dinner is one of the simplest changes to support better sleep and digestive calm.

Key take-homes & call to action

- Evidence is mounting: late dinners are more than a habit — they may be a metabolic stressor.

- The same calorie intake distributed earlier tends to beat a late-heavy strategy.

- Benefits may span weight, diabetes risk, cardiovascular markers, cancer risk, sleep and digestive health.

- In Australia, where discretionary food intake and metabolic disease are rising, timing tweaks may be an “easy win.”

- You don’t have to eat dinner at 5 pm — but every 15 minutes earlier may count.

If you experiment, do so gradually, monitor how you feel, and adjust to your lifestyle