Dr. Zelman first made the connection between liver disease and obesity in 1952.

He observed fatty liver disease in a hospital worker who drank in excess of twenty bottles of Coca-Cola daily. This was already a well-known complication of alcoholism, but this person did not drink alcohol.

It would be almost thirty years later, in 1980, that Dr. Ludwig at the Mayo Clinic described his experience. Twenty patients had developed fatty liver disease, similar to what is found in alcoholics, but they did not drink alcohol. This ‘unnamed disease’ was termed Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH), by which it is still known today. Again, the patients were all linked by the presence of obesity-associated diseases such as diabetes. In addition to enlarged livers, there was varying evidence of liver damage.

This discovery saved patients from their doctor’s repeated accusations that they were lying about their alcohol intake. Today, when patients have difficulty losing weight on an ‘Eat Less, Move More’ diet, doctors accuse patients about cheating, rather than accept the bitter fact that this diet simply does not work. This “Blame the Victim” game is clearly flawed.

· Overweight individuals have five to fifteen times the rate of fatty liver

· Up to 85% of type 2 diabetics have fatty liver

· Even in the absence of diabetes, those with insulin resistance alone have higher levels of liver fat

These three diseases clearly clustered together. Where you found one, you almost invariable found the others.

The deposition of fat in the liver where it should not be, is consistently one of the most important markers of insulin resistance. The degree of insulin resistance is directly related to the amount of fat in the liver.

The incidence of NAFLD in both children and adults has been rising at an alarming rate. It is the commonest causes of abnormal liver enzymes and chronic liver disease in the Western world. NAFLD is estimated to affect at least 2/3 of those with obesity.

This is a truly frightening epidemic. In the space of a single generation, this disease went from being completely unknown, with even a name, to the commonest cause of liver disease in the Western world.

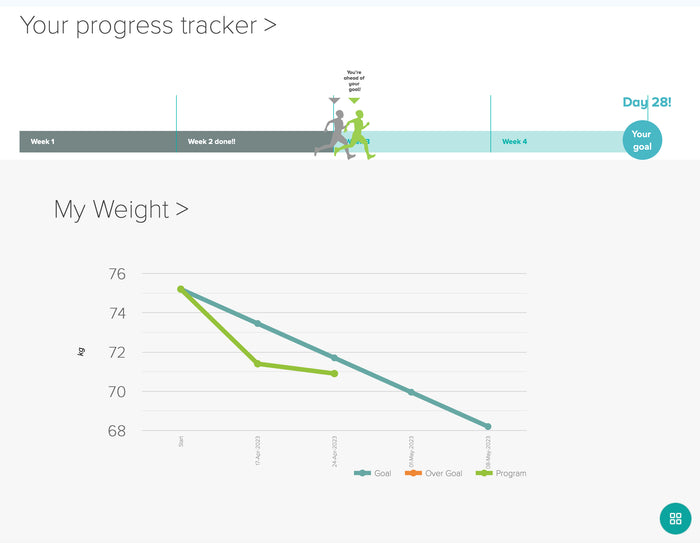

Interestingly, when we lose a significant amount of weight, even our organ size decreases. Note the size of the liver, heart, etc., in the image above ... not to mention the accumulation of visceral fat smothering the internal organs. As your organ size is considered part of your 'lean weight' in a body composition scan, you may not see a reduction in your overall fat percentage until you're a little closer to your goal weight.

How does this happen?

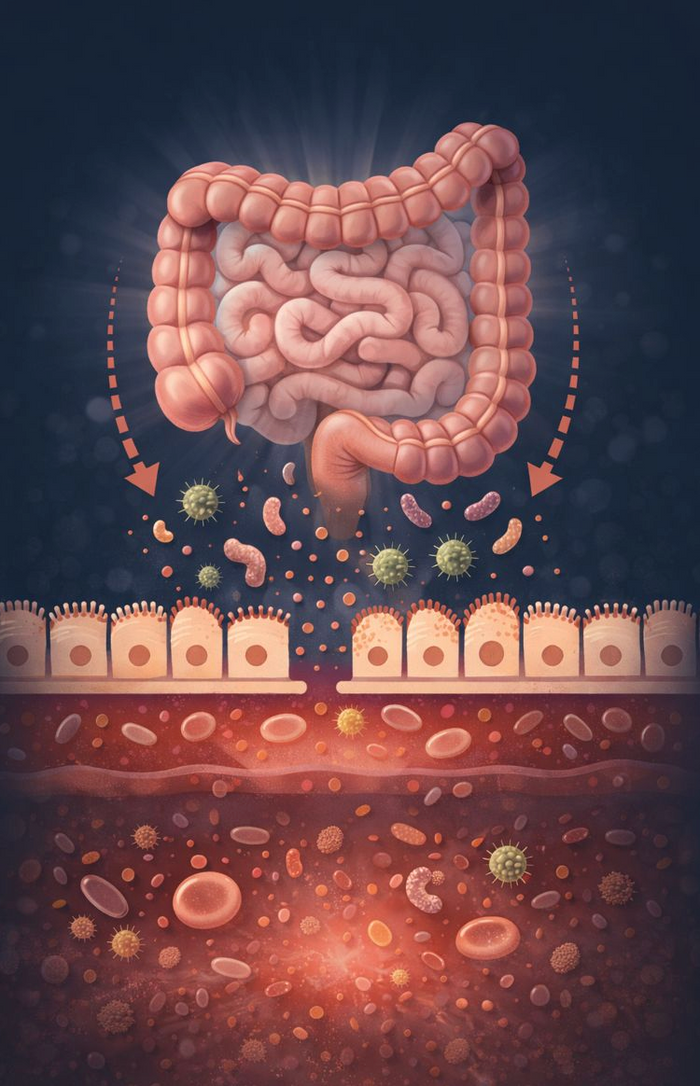

The liver lies at the centre of food energy storage and production. After absorption through the intestines, nutrients are delivered directly to the liver. Since body fat is essentially a method of food energy storage, it is little wonder that diseases of fat storage involve the liver.

Insulin pushes glucose into the liver, gradually filling it up. The liver converts this excess glucose to fat, the storage form of food energy. Too much glucose, and too much insulin, over too long a period of time leads eventually to fatty liver.

Insulin resistance is an overflow phenomenon, where glucose is unable to enter the cell that is already overfilled. Fatty liver, a manifestation of these overfilled cells, creates insulin resistance. The cycle proceeds as follows:

Too much insulin causes fatty liver.

Fatty liver causes insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance leads to compensatory high insulin levels

A vicious cycle.

Fat carried under the skin, called subcutaneous fat, contributes to overall weight, but has minimal health consequences. While it’s generally aesthetically undesirable, but it’s otherwise metabolically harmless.

Visceral fat is a far superior predictor of diabetes and heart disease. Fat within the organs other than the liver also plays a leading role in disease.

Fatty liver commonly precedes a diabetes diagnosis by ten to fifteen years. The emergence of the metabolic syndrome follows a consistent sequence. Weight gain, even as little as 2 kilos, is the first detectable abnormality, followed by low HDL cholesterol levels. High blood pressure, fatty liver, and high triglycerides emerge next, at roughly the same time. The very last symptom to appear was the high blood sugars. This is a late finding in metabolic syndrome.

In type 2 diabetic patients, there is a close correlation between the amount of liver fat and the insulin dose required reflecting greater insulin resistance. In short, the fattier the liver, the higher the insulin resistance.